Tom Girardi's CFO gets 10 years in prison as judge rejects credit for client payments

Christopher Kamon is going to prison while Girardi's wife, 'Real Housewives of Beverly Hills' star Erika Jayne, faces trial in a $25 million lawsuit from the bankruptcy trustee.

An accountant who helped disbarred lawyer Tom Girardi steal from seriously injured clients and their families was sentenced Friday to 10 years in federal prison after a judge rejected his lawyer’s argument that he should be credited for payments the clients received while they were being victimized.

Christopher Kazuo Kamon, 51, cried as he apologized for his crimes, but U.S. District Judge Josephine Staton said his statements “were rather vague” and his written letter falsely portrayed him “as a victim of the justice system.”

Staton said Kamon blamed Girardi for the crimes while ignoring his role as the “mastermind of an almost equally sophisticated scheme to steal millions from the Girardi case accounts.”

“He was following no one’s orders in stealing that money,” the judge said during a two-hour hearing in Los Angeles.

Kamon has been in jail since December 2022 after he was arrested as he returned to the United States from the Bahamas. He was charged with stealing millions of dollars from Girardi’s law firm in a scheme prosecutors say Girardi didn’t know about. He also was indicted alongside Girardi for the client fraud scheme that led a jury to convict Girardi of four counts of wire fraud last August.

Prosecutors say some of Girardi’s stolen money went to his wife, Real Housewives of Beverly Hills star Erika Jayne. The couple publicly separated in 2020, but their divorce has not been finalized and, according to trial testimony, they still are in contact.

Kamon spent his embezzled money on several homes, including one in the Bahamas where he hoped to live after Girardi’s fraud began to be publicly exposed. He also collected exotic cars, and his entrepreneurial endeavors outside Girardi Keese LLP included owning a company that rented portable stripper poles. He embezzled enough to pay his former girlfriend Nicole Rokita $20,000 a month — she called it an “allowance” when she testified in Girardi’s trial — and he paid for her to build a keto-friendly restaurant called Roketo that never opened.

The earliest stolen settlement in the indictment was a $53 million deal reached in 2013 with Pacific Gas and Electric Co. for the Ruigomez family over a gas explosion that badly injured Joseph Ruigomez and killed his girlfriend.

The other client victims were Josefina Hernandez, who never got anything from a $135,000 settlement reached in May 2020 for injuries related to a defective medical device, Judy Selberg, whose lawsuit over her husband’s deadly boat crash settled for $504,400. The fourth victim was Erika Saldana, whose lawsuit over her son’s catastrophic injuries in a car crash settled for $17 million. The boy died while Saldana still was trying to get her money from Girardi.

Prosecutors believe Girardi victimized many more clients. The California State Bar disclosed in November 2022 that it had received 136 complaints about Girardi between August 1982 and before the scandal erupted in December 2020, most involving client trust accounts. Girardi was disbarred in July 2022.

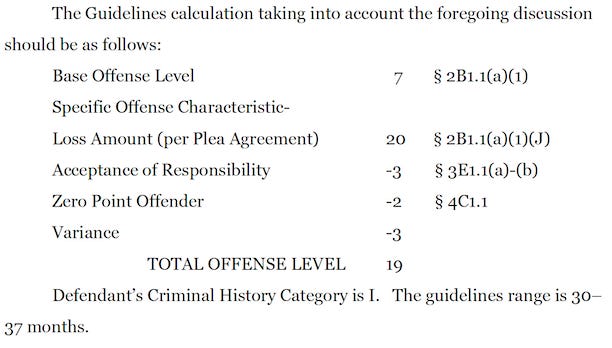

Kamon did not testify in Girardi’s trial. He pleaded guilty in October to two counts of wire fraud in a plea agreement that said prosecutors would recommend he be sentenced to the low-end of the applicable range under U.S. Sentencing Commission guidelines. Prosecutors also agreed that the loss associated with the frauds, which dictates the length of prison time Kamon faces under the guidelines, is between $3.5 million and $25 million.

Kamon’s lawyer Michael V. Severo of Pasadena argued prosecutors breached their agreement after U.S. Probation Office employees put the total loss at $26 million and didn’t credit Kamon for partial payments he made to the Ruigomez family. Severo also said prosecutors used “highly inflammatory language such as saying that defendant’s conduct ‘warrants a significant custodial sentence,’ and they included a letter from the court-appointed trustee overseeing the Girardi Keese bankruptcy in which the trustee called for Kamon to face “the maximum sentence.”

Prosecutors, however, said Staton should consider the total loss to be less than $25 million. They used separate enhancements for using sophisticated means and substantial financial harm to reach the same 121-151 month range that U.S. Probation did.

“The parties are absolutely in agreement: The defendants should be granted the benefit of his bargain,” Assistant U.S. Attorney Scott Paetty said on Friday.

Severo recommended Kamon be sentenced to 30 months in prison “or time served 28 months,” through a downward departure. Judge Staton on Friday called it “a dramatically below-guideline sentence.”

Staton ruled prosecutors adhered to their agreement, and she rejected Severo’s argument that Kamon should be credited for payments Girardi made to the client victims while he was lying to them about their lawsuit settlements.

“Payments would be made to make them happy so they wouldn’t report anything, so they could continue to steal from one client to give to the next client. Those were simply lulling payments,” the judge said.

Kamon was, however, credited for the payments when Staton ordered him to pay $2.3 million in restitution in the case with Girardi and $6.5 million in Kamon’s separate fraud case.

Staton said she was basing her sentence on the intended loss of the fraud instead of the actual loss. She also said an opinion last year from the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals didn’t decide the issue. Instead, the 2-1 decision in United States v. Hackett said using intended loss to calculate a stock promoter’s fraud sentence was not reversible error “given our precedent recognizing both actual and intended loss, and because there is a lack of consensus among the circuit courts on this issue.”

Kamon’s sentence comes as disgraced lawyer Michael Avenatti is scheduled to be re-sentenced next month in a federal wire fraud case for stealing from clients after the 9th Circuit vacated his 14-year sentence last October.

The three-judge panel ordered the trial judge to consider the value of Avenatti’s legal services when calculating the loss amount for his crimes. The panel also said Avenatti shouldn’t have been punished for the full amount of the settlements he embezzled when he was rightfully due some of the money under his retainer agreements with the clients. The opinion was unpublished, which means it’s not citable case law, and mostly about Avenatti’s attorney fees and not the lulling payments he made to clients.

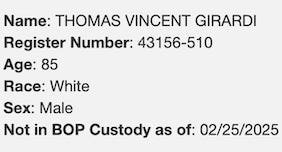

Girardi, meanwhile, is due in Staton’s courtroom on May 8 for a hearing on his mental status after he was evaluated at the U.S. Bureau of Prisons’ Federal Medical Center in North Carolina. Staton sent him there over his attorneys’ objections because of a federal law that says criminal defendants can be committed to a mental health facility instead of prison if their mental status requires it. He was released on Feb. 25. Prosecutors want him sentenced to 14 years in prison while his public defenders say he should stay in his assisted living center.

On Friday, Severo argued Kamon was being unfairly punished for Girardi’s actions when he never interacted with the clients and only wrote checks at Girardi’s request. He also said Kamon’s time in prison shouldn’t be increased for victim vulnerability and sophisticated means.

“What’s sophisticated about writing a check?” Severo asked on Friday. “If we’re going to go that route, every fraud is sophisticated, and I don’t think that’s the intent of the enhancement.”

Judge Staton said both enhancements apply when considering Kamon’s frauds together, particularly the sophistication of his own scheme against the firm. She also said Kamon’s letter to the court supports the enhancement for vulnerable victims because Kamon discusses the clients he brought to the firm.

Kamon knew the clients “had suffered catastrophic injuries” and needed money “to lead normal lives again,” Staton said.

Prosecution’s position:

Defense position:

U.S. Probation position:

Kamon told the judge, “I personally want to apologize to everybody affected.”

“Honestly, that’s all I can say after hearing everything today,” Kamon said.

He said his letter was his “effort to … try to show you I’m not a horrible person and I tried to correct this as best I can and make right for any wrong.”

“I don’t really understand this all completely, but I’m accepting of it. I just want to apologize,” Kamon said.

The trustee overseeing the Girardi Keese bankruptcy told Staton that Kamon has money hidden in Hungary and the Bahamas, including a home that’s losing value.

“We’re trying to get a hold of those assets for the benefit of the estate, for the benefit of the creditors, and we’re not getting cooperation,” said Elissa Miller, a partner with Greenspoon Marder LLP.

Miller emphasized that Kamon is responsible for his own crimes.

“There’s an amount of money that went to fund Mr. Girardi’s lifestyle, Ms. Jayne’s lifestyle, and then there’s an amount of money that went to fund Mr. Kamon’s lifestyle and his assets,” Miller said.

Judge Staton said letters from the victims “reveal the effects of the fraud far beyond just the loss of their settlement funds.”

“The client victims refer to the anguish suffered by being betrayed by those meant to protect them,” Staton said. “They indicate a loss of faith in a system that they believed was meant to protect them.”

Kamon’s side fraud also “perhaps reflects the defendant’s motivation in assisting Girardi in the main fraud,” Staton said.

Staton mentioned letters from Kamon’s family that discuss how he “supported and cared for his parents” and put others before himself. She said in her experience with white-collar fraud, the criminals “all seem to have taken good care of their family.”

Staton also said Kamon’s letter referred to himself as “being simply a 51-year-old man who made a mistake.”

“This was not one mistake. Instead, the defendant made a daily commitment to thinking of and acting in furtherance of his own financial interest to the detriment of others,” Staton said.

Kamon also is charged with federal crimes in the Northern District of Illinois related to Girardi’s embezzlement of settlement money from family members of victims of the deadly Lion Air plane crash in 2018. Severo said he’s considering a plea agreement that would recommend the judge allow Kamon to serve his sentence at the same time as his sentence in the Los Angeles case.

Trial in the Lion Air case is scheduled for July 14 before U.S. District Judge Mary Rowland in Chicago. A status conference is scheduled for May 15.

Erika Jayne, meanwhile, is fighting a lawsuit from Miller that seeks nearly $25 million that Jayne and her companies EJ Global, LLC and Pretty Mess Inc. received from Girardi Keese funds between 2007 and 2020.

“The Trustee further contends that the two corporate defendants were and are mere shells and the alter-ego of Ms. Girardi, and therefore Ms. Girardi is personally obligated for all obligations owed by the two corporate defendants to the Debtor,” according to a filing in U.S. Bankruptcy Court. “The Trustee also contends that Ms. Girardi knowingly and willingly participated in Mr. Girardi’s criminal enterprise and the money used to pay her business expenses were monies from that criminal enterprise.”

The case is with U.S. District Judge Anne Hwang in Los Angeles. A status conference is scheduled for June 4.

More court documents, including Kamon’s letter to Staton and his character reference letters, are available below for paid subscribers. Your paid subscriptions make my work possible.