LAPD argues man wrongfully convicted of murder isn’t due anything after 13 years in prison

Trial began Thursday in a 2016 lawsuit that's likely the last case the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals reassigned from U.S. District Judge Manuel Real before he died.

No one denies that Marco Antonio Milla spent 13 years in prison for a murder he didn’t commit. The now 40-year-old Los Angeles man was freed in 2014 based on the testimony of a federal informant, and a judge declared him factually innocent in a signed order.

But in the nearly 10 years since, the City of Los Angeles has refused to give him any money as attorneys argue his malicious prosecution claims are unfounded.

Now a federal jury is taking on a case that’s twice been to the 9th Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals, and a defense attorney told them on Thursday police can’t be blamed for following evidence that a judge and prosecutors also believed established probable cause for Milla’s arrest.

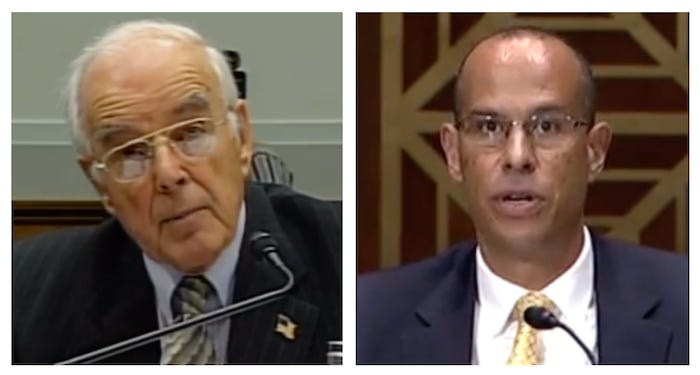

“They tried to meet with every alibi witness they could,” but none wanted to talk, Kevin Gilbert, a partner at Orbach Huff & Henderson LLP in Los Angeles, said in his opening statement. “No eyewitness ever ID’d another shooter.”

Gilbert said the case isn’t about whether Milla is innocent or guilty but about “what the detectives knew at the time, what they looked at in real time, not in hindsight, not after the fact.”

“The judge signed off on it and gave authorization not only to search Mr. Milla’s home, but also to go arrest him,” Gilbert said. Prosecutors then looked through what Gilbert called a “murder book” that detectives created detailing their investigation, and they decided charges were warranted.

But Milla’s attorney Martin Stanley said detectives “went searching for evidence to prove their story” and set their sights on Milla after noticing what they thought was a scar on his face in a photo lineup that matched a witness description of the man who shot three people in south Los Angeles in September 2001.

“The scar turned out to be acne, but by that time, the wheels were in motion,” Stanley said in his opening statement.

Stanley, a solo practitioner in Santa Monica, said police ignored Milla’s alibi, pressured witnesses and withheld information from prosecutors to secure a case. Had they obtained surveillance video from a liquor store in the City of Downey, “they would have found Marco Milla buying a beer at the time of the murder.”

“Marco Milla told them that. Why didn’t they go there?” Stanley said.

Expected to last through next week, the trial comes more than seven years into a lawsuit that has a marred history within the federal judiciary — including a rare reassignment order by the 9th Circuit — and is now on its third jurist. Witnesses will include Los Angeles County Superior Court Judge Olivia Rosales, who prosecuted Milla for murder while a deputy district attorney. She was appointed to the bench in 2009.

The shooting that led to Milla’s incarceration occurred on Sept. 29, 2001, shortly after boxer Bernard Hopkins beat Felix Trinidad for the world middleweight championship in a pay-per-view match. The fight was widely watched in the Hispanic community because Trinidad is from Puerto Rico and Hopkins is Black, Stanley told the jury.

The three victims who were shot were Black men, including Robert Hightower, who died. Gilbert told the jury that police knew the men were shot in a neighborhood controlled by gangs and rife with racial tensions between Blacks and Hispanics. They initially had another suspect in mind, Gilbert said, but no eyewitnesses identified him in photo lineups. Detectives turned to Milla after identifying him through photographs of local gang members, and they talked to one of the victims, Ramar Jenkins, who told them both verbally and in writing that Milla was the gunman.

“He remembered details. There were no ambiguities,” Gilbert said. “He was very clear and very certain.”

Stanley said Jenkins will testify to feeling pressured by detectives.

“He’ll tell you he’s been feeling bad about this for the last 20 years,” Stanley told the jury.

A Los Angeles jury convicted Milla of one count of murder and five counts of attempted murder on Dec. 23, 2002, and he was sentenced to life in prison in August 2003. In November 2010, the Los Angeles District Attorney’s Office notified Milla’s lawyer of a reliable confidential source in a U.S. Homeland Security investigation who said the wrong man had been convicted of Hightower’s murder.

The source said members of the 204th Street gang had gathered at the home of a member named Psycho Mike to watch Trinidad fight Hopkins. Everyone went outside after Hopkins won and someone gave Julio “Downer” Munoz a gun before shots were fired, according to Stanley’s federal complaint.

The source “also stated that, to his knowledge, Petitioner (Marco Antonio Milla) was not present in the area … at the time Robert Hightower was shot,” according to the complaint.

Stanley said on Thursday that Milla was at his girlfriend’s apartment in Downey, about a 30-minute drive from the shooting scene, to watch the boxing match. His girlfriend couldn’t get her pay-per-view to work, Stanley said, and Milla was unaware Hopkins had won when he walked to the nearby liquor store to buy alcohol.

Milla used the information from the federal informant in a Los Angeles County Superior Court habeas petition that led to an evidentiary hearing and then an order for new trial.

“When granting the writ of habeas corpus, the court explained, among other things, that the testimony of the [source of information] constituted newly discovered evidence; that the testimony of the SOI was credible; that Downer, who took the stand and refused to testify pursuant to the Fifth Amendment, more closely matched the description of the shooter than the Plaintiff, in that Downer is slender and slight of stature and has a scar on his left forehead and Plaintiff has a much larger frame and es not have the aforementioned scar.”

Milla was released from prison on Aug. 11, 2014, and prosecutors dismissed all charges instead of pursuing a second trial. He secured a finding of factual innocence in 2015. No one else has been prosecuted for Hightower’s murder or the other shootings.

Milla first sued in Los Angeles County Superior Court in 2015, but his case was moved to the federal Central District of California. The defendants are the City of Los Angeles and the detectives who investigated him, John Vander Horck, who died in 2020, and Robert Ulley, now an LAPD lieutenant who’s seated at the defense table with Gilbert.

The 9th Circuit ordered the case reassigned from U.S. District Judge Manuel Real in February 2019 — four months before Real died — after the 1966 Lyndon B. Johnson appointee granted the city’s summary judgment motion without a hearing, which the appellate court said “raises real doubts as to the care with which Milla’s claims were examined.”

Then in February 2022, 9th Circuit overturned another summary judgment by the new judge, U.S. District Judge Stephen Wilson, who like Real didn’t hear oral argument before issuing his order.

Unlike Real, though, Wilson doesn’t have a storied history of being booted from cases by the 9th, and the 9th didn’t order him off the case. But the 1985 Ronald Reagan appointee got rid of it himself by transferring it to U.S. District Judge Fred Slaughter, a 2022 Joe Biden appointee, as part of the Central District’s standard calendar-building procedure for new judges.

Slaughter’s courtroom is in Santa Ana instead of Los Angeles, so the eight jurors who are to decide the validity of Milla’s claims live in Orange County, not the Los Angeles area.

They heard Thursday from Milla as well as Mitchell Eisen, a Cal State LA professor who testified as an expert witness about photo lineups and witness memory.

First, jurors heard in Gilbert’s opening about Milla’s May 2001 arrest for allegedly pointing a gun at a Black man’s head a block from where the September shooting occurred. Gilbert said Milla was never charged because the victim wouldn’t testify and there was no corroborating witness, “but the detectives were aware of that May arrest” when they were investigating Milla for the shooting.

In his direct-exam, Stanley asked Milla if he’d pointed a gun at the man.

“Did you do that?” Stanley asked.

“No, sir,” Milla said.

Stanley also questioned him about Gilbert’s statement that he was stopped by police in the area of the shooting in the days after, and he asked about his arrest.

“Did you, like, try to put up a fight at all?” Stanley asked.

“No sir,” Milla answered.

“Did you try to run at all?” Stanley asked.

“No sir,” Milla answered.

“Did you have any idea why the police were there before they arrested you?” Stanley asked.

“No sir,” Milla answered.

Milla’s testimony was surprisingly brief. Shockingly so, actually. I was expecting a deeper narrative about his experiences during the investigation and at least a little bit about his 13 years in custody, even if there would be sustained objections for relevance. But his direct-exam was only about 20 minutes, and it felt a little scattered.

Stanley hasn’t made a specific damages request, but he mentioned “millions and millions of dollars” during voir dire. The trial is expected to last into next week.

Case documents are available below for paid subscribers, including the complaint, Judge Real and Judge Wilson’s summary judgments, Judge Slaughter’s 29-page order on motions in limine and several of the motions and oppositions. Your paid subscriptions make my work possible.