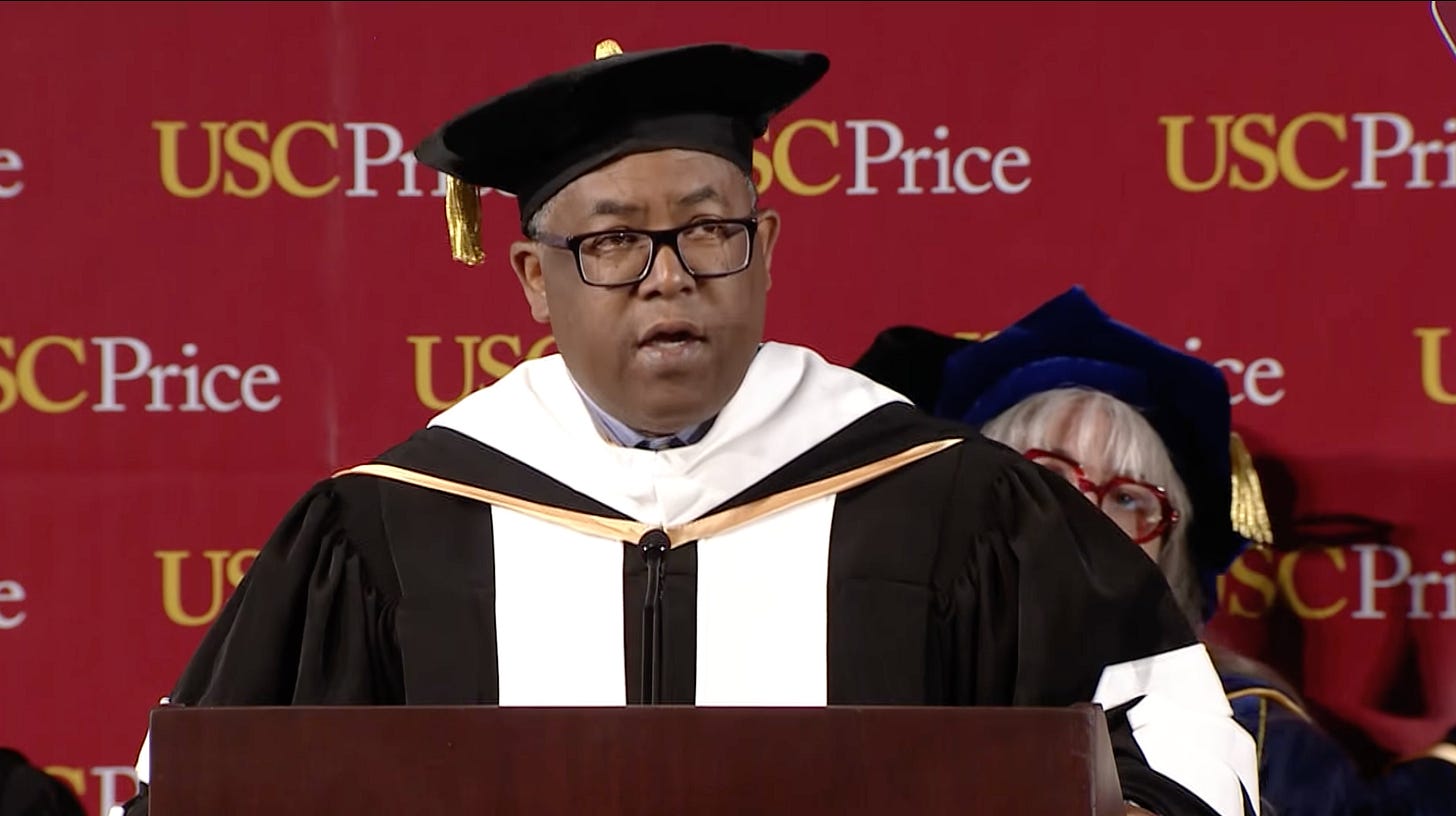

Jury hears prosecutor's final account of Mark Ridley-Thomas' evolving USC bribery scheme

From a 'wink and nod' to a 'push and shove,' the longtime Los Angeles politician's communications with USC School of Social Work Dean Marilyn Flynn evolved in 2017.

Jurors in Mark Ridley-Thomas’ corruption trial got a final look on Friday at how his correspondence with a University of Southern Califo…