Jury acquits Texas school police officer of child endangerment in trial over mass school shooting

Adrian Gonzales was accused of a crime for each of the 19 children who were murdered and 10 who were injured on May 24, 2022, by a gunman who was killed by law enforcement.

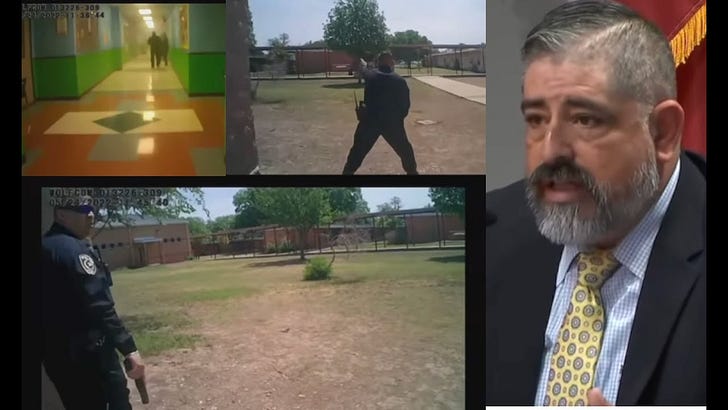

A jury in Corpus Christi, Texas, on Wednesday acquitted former Uvalde school police officer Adrian Gonzales of criminal charges for his response to a gunman who went on to murder 21 people inside an elementary school.

Jurors deliberated about seven hours before finding Gonzales not guilty of all 29 counts of child endangerment or abandonment. He appeared to be trying not to cry as he hugged his attorneys.

He told reporters he wanted to “start by thanking God for this, my family, my wife and these guys right here,” referring to his attorneys.

“He put them in my path, you know, and I’m just thankful for that,” Gonzales said

“Anything you want to say to the families?” a reporter asked.

“No. Not right now,” Gonzales said.

Jesse Rizo, whose 9-year-old niece, Jackie Cazares, was among the 19 children murdered, told reporters that “faith is fractured, but you never lose faith.”

“You don’t lose faith because these children that are no longer with us that are at the cemetery, they can’t speak for themselves. We speak for them. We fight to the end. And as hard as it is, you know they deserve it,” Rizo said.

“The teachers — Irma [Garcia], Eva [Mireles] — they had nothing on them, except for valor, except for courage, and they fought to the end. They pushed back hard. They gave their life," Rizo said.

He mentioned “those poor little survivors that have to live with the nightmare” and said he wonders how some of the responders “look at themselves in the mirror.”

“The man let me down. You can’t paint the an image and portray him as some kind of hero,” Rizo said.

He said he was “very hopeful” for a guilty verdict.

”We have children at stake, absolutely innocent children that did everything that they were trained to do, hide, turn the lights off, but the officer that was trained ... to go towards the shooter, to listen for the gunshot. And what does he do? Sit back ... for a minute and change while the massacre continues to happen,” Rizo said.

Brett Cross, whose 10-year-old son, Uziyah Garcia, was murdered, said he “can't tell what's going to happen, but we’ve got to get it right.”

“If not for us, if not for our kids, I just want people to start acting for their own,” Cross said.

“Why is your presence here at the courthouse important?" a reporter asked.

“Because I made a promise to my son that I would never stop fighting,” Cross said. “This country, the state, already made a liar out of me once when I swore to him that I would never let anything bad happen to him ... The city, the school, the state, the gun industry, they all made liars out of me. Nothing will make a liar out of me when it comes to fighting for my son.”

Gonzales was charged with a crime for each of the 19 children who were murdered and 10 who were injured alongside two teachers on May 24, 2022, in a fourth grade classroom building at Robb Elementary School in Uvalde, about 85 miles west of San Antonio.

Prosecutor Bill Turner told jurors in his closing argument that their verdict “will set the bar for law enforcement in these situations: if it’s appropriate to stand outside hearing the 100 shots while children are being slaughtered.”

“That is your decision to tell the state of Texas,” Turner said. “And by the same token, if that is not appropriate, if that is not how we expect officers that are charged with the duty of protecting children to act, that will also go out from this court.”

The doors to the classrooms were unlocked when the gunman entered because of school-issued magnet meant to halt locks and allow uninterrupted entries and exits from students and staff. Teacher Mercedes Salas, however, testified that she didn’t use a magnet and instead always kept her door locked. She heard the gunman, who was a former student, pound on her door before he went to the other classrooms and opened fire.

Turner distinguished the unlocked doors from Gonzales’ conduct because no children were in “imminent danger” when teachers decided to leave the doors unlocked.

“That failing to act — failing to lock the doors — did not happen as the gunman was firing guns. The children weren’t in imminent danger, immediate,” Turner said.

Turner said two groups have a duty to protect children under the Texas statute criminalizing child endangerment or abandonment: parents and police officers.

“The charge in this case is that these 29 children were in danger. Not just danger, but imminent, immediate, close-at-hand danger, and that there was a man who had a duty to act, who failed to act,” Turner said.

In trial, Gonzales’ lawyers at LaHood Norton Goss Law Group, PLLC, in San Antonio said he responded as best he could based on the information he had at the time. They tried to refute prosecutors’ argument that he missed a chance to stop the gunman from going into the school, and they compared his actions to the actions of other officers who have not been charged with crimes.

They called two defense witnesses after prosecutors rested their case on Tuesday: Guillermo “Willie” Cantu, a retired special weapons and tactics officer with the San Antonio Police Department who defended Gonzales’ actions, and Claudia Rodriguez, a secretary at a funeral home across from the school who testified about the gunman hiding between cars in the school parking lot. Jurors saw surveillance video, and Rodriguez testified the gunman was ducked down reloading and not visible to Gonzales.

Gonzales’ attorney Jason Goss said during the post-verdict press conference late Wednesday that the situation is “obviously very emotional” for Gonzales. The “wall of people” in front of him “has been reporting ever since Adrian was charged that he failed to do his duty, because that’s what the prosecutors charged.”

“And the evidence showed that that wasn’t true,” Goss said.

Goss didn’t dispute that Gonzales owed a duty to the children.

“Of course there is. He was doing his duty. He was running to the danger. He was driving right in there,” Goss said.

Prosecutors “just ignore all of his actions because they’re trying to pretzel it, massage it, get it in there, do anything that they can to get the conviction.”

Goss, who split the defense argument with Nico LaHood, told jurors that Gonzales “was trying” and was one of the first five officers inside the school. He was there when the gunman fired through a classroom door and shot two officers, and he drove toward the danger searching for the gun before he went into the school.

The jury’s verdict “is not going to make [law enforcement] perfect the next time,” Goss said. “It’s not going to make them not make mistakes. It’s not going to make them not interpret things differently, strangely, weirdly based on their own experiences.”

He called it “one of the most horrible things that’s ever happened in this state that those kids are not served.”

“The memory of those children, that I agree should be honored, is not honored by an injustice in their name,” Goss said.

LaHood followed Goss’ 37-minute argument with a 43-minute argument that included him honoring the Lady Justice allegorical persona and her scales of justice.

“These scales say, ‘I don’t care about those cameras.’ These scales say, ‘I don’t care about the false narrative that’s been out there.’ These scales say, ‘I don’t care about all the resources of the government.’ The scales even say it doesn’t even matter what the judge thinks,” LaHood said. “The scale says … we have to balance all that out, look at everything and come find this concept called justice. And I love it. I love her.”

He compared Gonzales’ actions to the actions of other officers and said if Gonzales and the four officers he was with first “hadn’t contained the shooter, he could have done the same thing to the whole school. Think about that.”

LaHood told jurors that prosecutors are trying to serve them “a coward sandwich” they want them to believe is made by Gonzales, but that is surrounded by slices of bravery.

“You have this coward sandwich, but you have bravery and bravery around it. The bravery of driving into trouble, thinking there was a shooter,” LaHood said.

LaHood echoed Goss’ argument that Gonzales’ prosecution could deter law enforcement from taking future action.

“That’s not the message that needs to be sent. They need training. They need good training. They need proper training. They need resources. They need help from those schools to work with them in conjunction,” LaHood said.

LaHood said prosecutors want jurors “to ignore that Adrian drove into danger.”

“Remember that sandwich? They’re gonna say, ‘Yeah, okay, the bread, the bread is fine, but the coward sandwich is full in the middle’, and then, ‘yeah, I understand the bread at the end is bravery, but we just want you to focus on what’s in the middle,’” LaHood said.

He said it’s “like an Oreo.”

“They want you to have the coward cream in the middle,” LaHood said.

Rizo, whose niece was killed, referenced LaHood’s metaphor when talking to reporters after the acquittal. He said his message for Gonzales is “don’t be fooled by your attorney.”

“Your attorney can talk about sandwiches. Sandwich of coward, that there’s something on the outside and the bread? It’s insulting, to be honest with you,” Rizo said.

LaHood said at the press conference that he understands victims’ families are upset.

“I’ve been praying for them. We pray for them. We’re sorry that they feel that way. We understand that their separation from their loved one is going to be felt as long as they walk on this earth,” LaHood said. “We don’t ignore that. We acknowledge that. We’re just going to continue to pray for them. So I’m very sorry that they feel that way.”

LaHood said jurors told the defense team after the verdict that they saw “gaps in the evidence.”

“They appreciated us bringing out those gaps. They considered everything. They were very diligent. They worked very hard back there. They were very mindful and deliberate,” LaHood said.

“We felt Adrian was innocent from the beginning. When we analyzed the situation, we knew it was going to be a challenging case because of the emotions, the sheer emotions behind it, and those precious babies being taken from those families,” LaHood continued.

Christina Mitchell, the district attorney for Uvalde and Real counties in Texas, began her 17-minute rebuttal by defending her decision to prosecute Gonzales. She referenced other investigations into the police response to the shooting.

“The easiest thing would have been me to do what all those did, which is say, don't blame us. Blame somebody else, or everybody’s to blame, therefore you can’t hold anybody responsible. That would have been the easiest thing,” Mitchell said. But, “I’ve never bowed to political pressure, and that’s not what this case is about.”

Mitchell said she wants to send a message “that when you are a peace officer for a school district, and you raise your right hand and say, ‘I am going to be a peace officer’ … you’re going to be held responsible. You’re going to be held to that duty.”

“We are basically teaching these kids, and the kids in room 111 and room 112 were taught, to practice for their impending death. You don’t cry and you don’t scream, but we’re going to teach you what you do when a monster makes his way into the school. We’re going to have you rehearse your own death,” Mitchell continued. “But yet, we have active shooter training that says to go to the fire, that the defendant taught, but we’re going to ignore that, because on any given day, if he says, ‘not my day,’ we’re supposed to just look the other way.”

She ended her rebuttal by telling the jury, “We cannot let 19 children die in vain and another 10 to suffer. They’re going to be that - suffering for a long time. On behalf of those 19 children, I respectfully request that after your deliberations, that you return a verdict of guilty.”

Highlighting the differences in state’ judicial systems, Brian Gurwitz, a criminal defense attorney in Orange County, California, commented on my Facebook clip of Mitchell, “I don’t know about Texas, but it would be clear prosecutorial misconduct to argue that a reason for the jury to vote guilty is to ‘send a message’ to other officers.”

Pete Arredondo, Gonzales’ boss at the Uvalde Consolidated Independent School District Police District, is awaiting trial on 10 counts of child endangerment or abandonment. While the case against Gonzales alleged he endangered all 29 children, the case against Arredondo says his decisions prolonged the danger and suffering of the 10 injured children.

You can read about the testimony from all witnesses in my previous articles:

The victims were:

Uziyah Garcia, 10

Eliahna Amyah Garcia, 9

Xavier Lopez, 10

Amerie Jo Garza, 10

Jose Manuel Flores Jr., 10

Alithia Ramirez, 10

Annabell Guadalupe Rodriguez, 10

Eliahna A. Torres, 10

Jacklyn “Jackie” Cazares, 9

Jayce Carmelo Luevanos, 10

Jailah Nicole Silguero, 10

Makenna Lee Elrod, 10

Layla Salazar, 11

Maranda Mathis, 11

Nevaeh Bravo, 10

Tess Marie Mata, 10

Rojelio Torres, 10

Maite Yuleana Rodriguez, 10

Alexandria “Lexi” Aniyah Rubio, 10

Eva Mireles, 44

Irma Garcia, 48

Thank you for supporting my independent legal affairs journalism. Your paid subscriptions make my work possible. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please consider purchasing a subscription through Substack. You also can support me through my merchandise store and by watching my YouTube channel. Also, please follow me on Facebook and Instagram as I grow my Meta presence. Thank you!