Judge rejects DOJ's post-sentencing dismissal request in police civil rights case

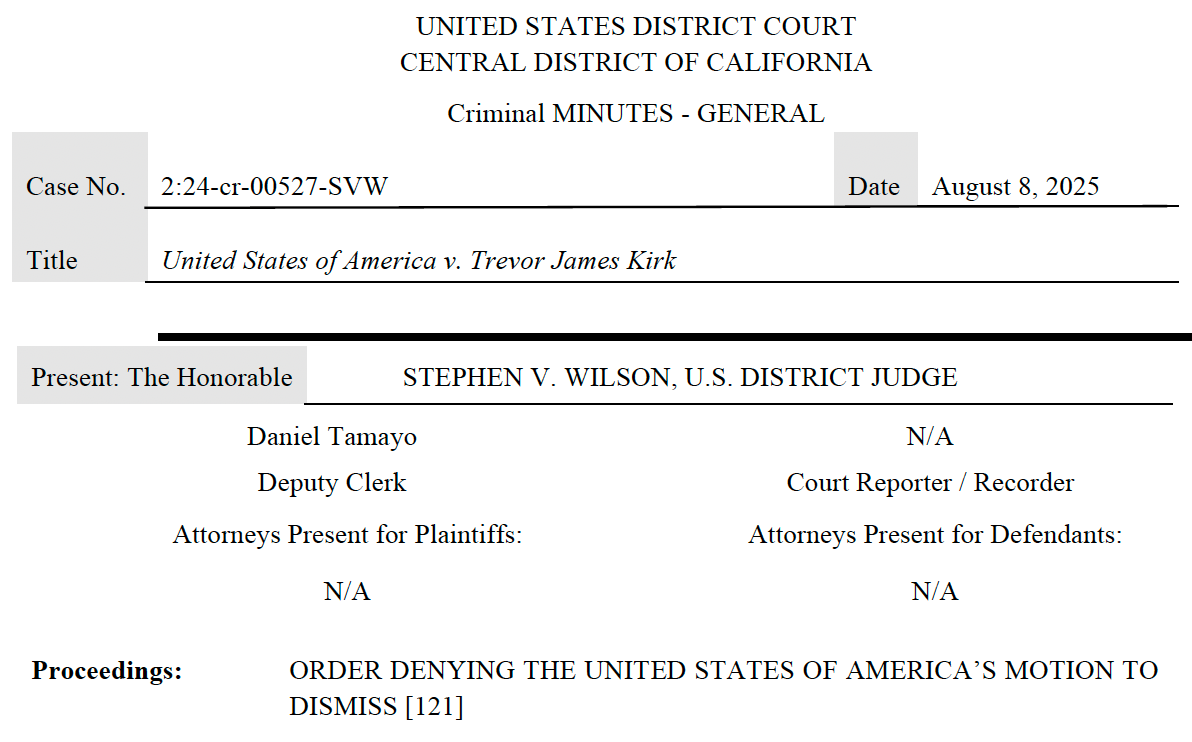

Ex-Deputy Trevor Kirk is to report to prison in Aug. 28 after U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson said dismissing his criminal case is "contrary to the public interest."

Calling the U.S. Department of Justice’s request “contrary to the public interest,” a judge has declined to dismiss a criminal case against a former Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy already convicted and sentenced to prison for violating a woman’s civil rights through excessive force.

Prosecutors want the indictment dismissed not because they reconsid…