Judge disqualified from rapper's murder case after defense cites 'hostile comments', 'obvious bias'

An attorney for Alicia Andrews, who is awaiting sentencing for manslaughter for rapper Julio Foolio's fatal shooting, plans to cite the disqualification when asking for a new trial.

An appellate court in Florida this week removed a judge from a high-profile murder case after a defense lawyer complained of “hostile comments” and “obvious bias.”

Alicia LaToya Andrews’ lawyer plans to seek a new trial after Florida’s 2nd District Court of Appeal agreed that Judge Michelle Sisco shouldn’t sentence Andrews for her manslaughter conviction over the fatal shooting of rapper Charles “Julio Foolio” Jones in Tampa in June 2024.

Jeremy McLymont, founder of AsiliA Law Firm, P.A in Miami, told me the appellate court made “the right decision.”

“Everyone is entitled to a fair trial, including Ms. Andrews. We are convinced that a new trial should and will be granted after some litigation at the trial and or appellate level,” said McLymont, a former assistant public defender in Miami-Dade County whose other clients include Milagro Cooper, the online commentator sued for defamation by rapper Megan Thee Stallion.

Andrews’ trial was streamed online, and McLymont included with his petition 16 videos clips as exhibits. He told me the recordings “helped immensely.”

“You could never capture the mannerisms, the tone etc. through a transcript,” McLymont said. “It would have been harder with a transcript, but it has been done before.”

Sisco is a former assistant Florida state attorney with the Hillsborough County State Attorney’s Office who has been a judge since 2002. She earned her law degree from the University of Florida College of Law in 1991.

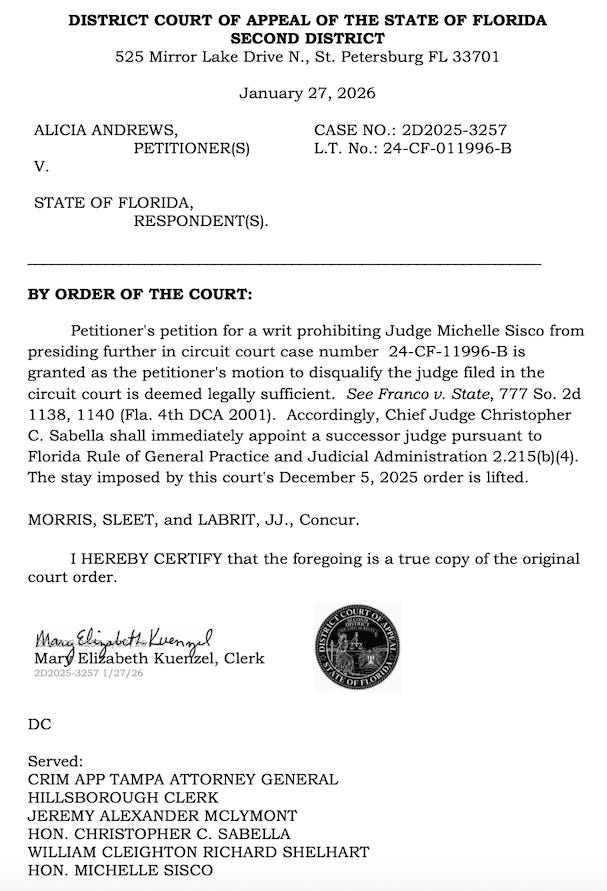

The order from the three-judge panel deemed McLymont’s petition to disqualify her from Andrews’ case “legally sufficient” and ordered Christopher C. Sabella, the chief judge of Florida’s 13th Judicial Circuit where Sisco presides, to appoint a new judge “immediately.”

The three-sentence order does not explain the judges’ reasoning, but McLymont’s 18-page petition argued the judge abandoned “cold neutrality” and “did everything in its power to ensure that Ms. Andrews was convicted” by humiliating defense counsel in front of the jury, assisting prosecutors, treating defense witnesses more harshly than prosecution witnesses and pressuring the defense to hurry its case presentation.

“Ms. Andrews maintains that she has a reasonable fear that the trial court has abandoned its role to be an impartial arbiter,” McLymont wrote. “Ms. Andrews’ fear is confirmed by thousands of people who watched the trial online.”

Andrews, who will be 23 next week, is the first of five defendants to be tried for Jones’ murder. Her boyfriend, Isaiah Chance, is in jail awaiting trial with codefendants Sean Gathright, Rashad Murphy and Davion Murphy. Prosecutors did not seek the death penalty against her like they are against the four men.

Surveillance videos show three gunmen — whom prosecutors allege are Gathright and the Murphy cousins — ambush Jones with two AR-style rifles and Glock 19 as he sat in his Dodge Charger outside a hotel near the University of South Florida early on June 23, 2024. Chance and Andrews were nearby in the same parking lot. Prosecutors in trial argued she helped plan Jones’ murder, including following him as he celebrated his 26th birthday in the hours before he died.

Jones was prominent in Jacksonville in drill rap, a subgenre of hip-hop music, and his music videos showed him celebrating the murders of rivals by pouring champagne on their graves. He was shot several times in Houston, Texas, in July 2023, and testimony in Andrews’ trial indicated the same firearm that injured him then was used to murder him a year later.

A jury on Oct. 31 acquitted Andrews of first-degree murder and conspiracy to commit first-degree murder but convicted her of manslaughter, which was a lesser included charge to murder.

Judge Sisco scheduled her sentencing for Dec. 8 and declined to stay it before she rejected McLymont’s disqualification motion. The appellate court, however, on Dec. 5 granted McLymont’s request to stay sentencing and gave prosecutors 30 days to “show cause” for why Sisco shouldn’t be removed.

Judges Robert Morris, Daniel H. Sleet and Suzanne Labrit granted the petition on Tuesday (Jan. 27).

Petition details judge’s comments and ‘coaching’

McLymont’s video exhibits included Judge Sisco not allowing cross-examination about a firearm’s safety mechanism and allowing prosecutors’ “hostile and prejudicial commentary” toward him and his co-counsel.

In one exhibit, the judge accused defense counsel of “lying and falsely asserting” that the lead detective watched the case online when McLymont had only said he wanted to ask the detective if he had.

McLymont also cited the judge’s response when he inquired in front of the jury about her reason for sustaining an objection. McLymont had asked Detective Juan Ramos of the Tampa Police Department, “It’s not that you didn’t have a way to verify—it’s that you just didn’t try to do it?”

McLymont told Sisco, “I don’t even understand the objection for ‘argumentative’ on cross” and, as the recusal petition describes it, “she dismissed counsel outright, took off her glasses, sat up in her chair and snarled ‘Well, I understand it, and I sustained the objection.’”

McLymont’s recusal petition said Sisco’s “public rebuke served only to belittle Defense Counsel and reinforce to the jury that the court disapproved of his questioning, which was by no means improper.”

“Florida courts have repeatedly recognized that a judge’s visible hostility toward counsel, especially before the jury, justifies disqualification,” McLymont wrote.

I included the exchange in a clip about McLymont pushing back on Judge Sisco sustaining objections, and it drew a large number of views on Instagram from lawyers who debated in the comments who was correct.

McLymont also cited Judge Sisco’s admonishment of his co-counsel Yselly Herrera when she “attempted to speak on behalf of the defense.” Sisco told Herrera, “I didn’t ask you to talk” and told her she needed permission to speak.

“The trial court never required the State to ask for permission to speak, or interject, or voice their opinions throughout the course of the trial,” McLymont said. “The trial court was merely taking its frustrations out on the Defense and attempting to humiliate Ms. Herrera in public.”

McLymont’s petition also said Sisco sought to humiliate defense by challenging his “competency and integrity” when he sought to admit evidence through a flash drive.

The judge said he couldn’t introduce it as evidence then “instead of acknowledging her mistake, the trial court searched for other reasons to challenge the admission of the evidence.”

The petition quoted Sisco asking McLymont, “What else is on the flash drive?” and said the judge “continued challenging counsel’s integrity in front of the jury by telling the State that they needed to look at the flash drive before it went back to the jury to make sure there was nothing on the flash drive that should not be on the flash drive.”

“Throughout the trial, the State introduced several items of digital evidence in the form of a compact disc ‘CD’. The trial court never challenged the State’s integrity and trustworthiness, or its ability to introduce such evidence,” McLymont wrote.

Judge Sisco also interrupted McLymont’s closing argument and said testimony he was referencing should have been objected to because it’s irrelevant, which McLymont’s petition said left “the jury with the impression that Defense Counsel was making improper arguments.”

“The trial court’s repeated comments, coaching-style interventions, and directives to the State demonstrate exactly the type of judicial participation Florida courts have found incompatible with due process,” McLymont wrote. “The trial court’s conduct conveyed distrust of Defense Counsel, suggested impropriety where none existed, and unmistakably signaled alignment with the prosecution.”

McLymont argued the judge also unfairly allowed prosecution witnesses to testify without their faces being shown on camera while not allowing defense witnesses to do so. He also cited her comments to a witness who refused to identify people in a photograph she said weren’t involved in the case. The judge told the witness, “You’re refusing to give their names? You’re under oath to tell the truth.”

“When the witness reiterated that these individuals were unrelated to the case, the trial court retorted, ‘Well I guess you’re the judge now.’ The witness explained that the witnesses ‘were not involved in this’ and the trial court in a sarcastic and demeaning tone said, ‘uh-huh,’” according to the petition.

Judge Sisco also sustained a hearsay objection when the witness said she’d been advised not to identify certain people, then told her, “Nope, nope, nope. I sustained the objection. You can’t answer it. You’re not actually the judge in here … you need to do what I tell you to do.”

“Instead of politely explaining to the witness what it means to sustain an objection, the trial court chastised the witness in front of the jury. This unnecessary and demeaning exchange again signaled to the jury that the witness was defiant or untruthful,” McLymont wrote.

McLymont also cited Judge Sisco’s comments to the jury about the length of the trial. She said during the prosecution’s case in chief that the jury would get the case by the end of the week, which McLymont argued “compressed or curtailed the Defense’s presentation of evidence.”

McLymont said the judge pressured him to rush his cross-exam of the lead detective, and her “comments and conduct made clear that it intended to end the trial regardless of whether the Defense had sufficient opportunity to call witnesses, conduct examinations, or introduce evidence.”

The petition cited a 1986 Florida Supreme Court case, Fischer v. Knuck, that said a judge should be disqualified if their heavier causes a reasonable fear of impartiality, including through pressured or uneven trial management.

“Here, the court’s assurances to the jury, coupled with its repeated efforts to hasten the proceedings while the Defense had yet to begin its case, created the unmistakable impression that the outcome of the trial was being prioritized over the process. This further supports the conclusion that the court’s actions, viewed cumulatively, justify disqualification,” McLymont wrote.

Opposition argues the judge was correct

In response, Florida Assistant State Attorney General William Shelhart argued McLymont raised only four examples that “do not demonstrate judicial bias” but rather “reflect the appropriate expertise of the court’s discretion and authority.”

He said the examples are:

“the court sustaining the State’s objection to a question posed by the defense during its cross-examination of the FDLE analyst and declining a request for a sidebar to discuss further”

“the court’s handling of the defense request to introduce photographs via a flash drive”

“the court assuring the jury that they would have the case by Friday, October 31, 2025, as discussed during voir dire”

“the court asking the defense to fast forward the previously published-in-full one hour and twenty-two minute interrogation video to the portion pertinent to the defense cross-examination”

The first complaint “merely takes issue with an adverse ruling,” and Shelhart said the judge was correct that McLymont’s question was irrelevant and right to address him in open court. While the witness discussed firearm safety in direct-exam, “this statement related to the handling of the murder weapon in a crowded courtroom and was made to ensure court personnel and the public that the firearm could not be discharged.”

Regarding Sisco’s comments about the false drive, Shelhart said the judge“correctly confirmed that during deliberation the jury would only have access to evidence admitted at trial.” Sisco “reasonably questioned why the defense presented the photographs on a flash drive when they were easily capable of being printed and admitted into evidence in their physical form.”

“This inquiry was a proper exercise of a legitimate judicial function,” Shelhart wrote.

Shelhart said McLymont’s final two complaints about Judge Sisco rushing the trial “both have to do with respecting the time of the court, the parties to the proceeding, and the empaneled jurors.”

McLymont replied that his petition raised four issues with Judge Sisco and cited 14 examples, not merely four examples as Shelhart said.

“The State failed to respond to three of the four issues raised by Ms. Andrews. Instead, the State created its own arguments for Ms. Andrews and responded to those arguments,” McLymont wrote.

The Florida appellate justices who granted McLymont’s petition cited a 2001 case, Franco v. State, in which a Florida 4th District Court of Appeal panel reversed a trial judge’s decision not to disqualify himself from a murder case and said his “facial gestures and conduct exhibited a lack of control and lack of judicial temperament.”

“A trial court’s prejudice against an attorney may be grounds for disqualification when such prejudice is of a degree that it adversely effects the litigant,” the judges said then.

Andrews’ case had not yet been assigned to another judge as of late Wednesday.

You can watch videos from Andrews’ trial on my YouTube channel.

Court documents:

Dec. 4 disqualification petition

Jan. 5 state’s response

Jan. 20 reply to response

Previous article:

Thank you for supporting my independent legal affairs journalism. Your paid subscriptions make my work possible. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, please consider purchasing a subscription through Substack. You also can support me through my merchandise store and by watching my YouTube channel. Also, please follow me on Facebook and Instagram as I grow my Meta presence. Thank you!