9th Circuit says victim in civil rights case has no right to challenge dismissal of felony

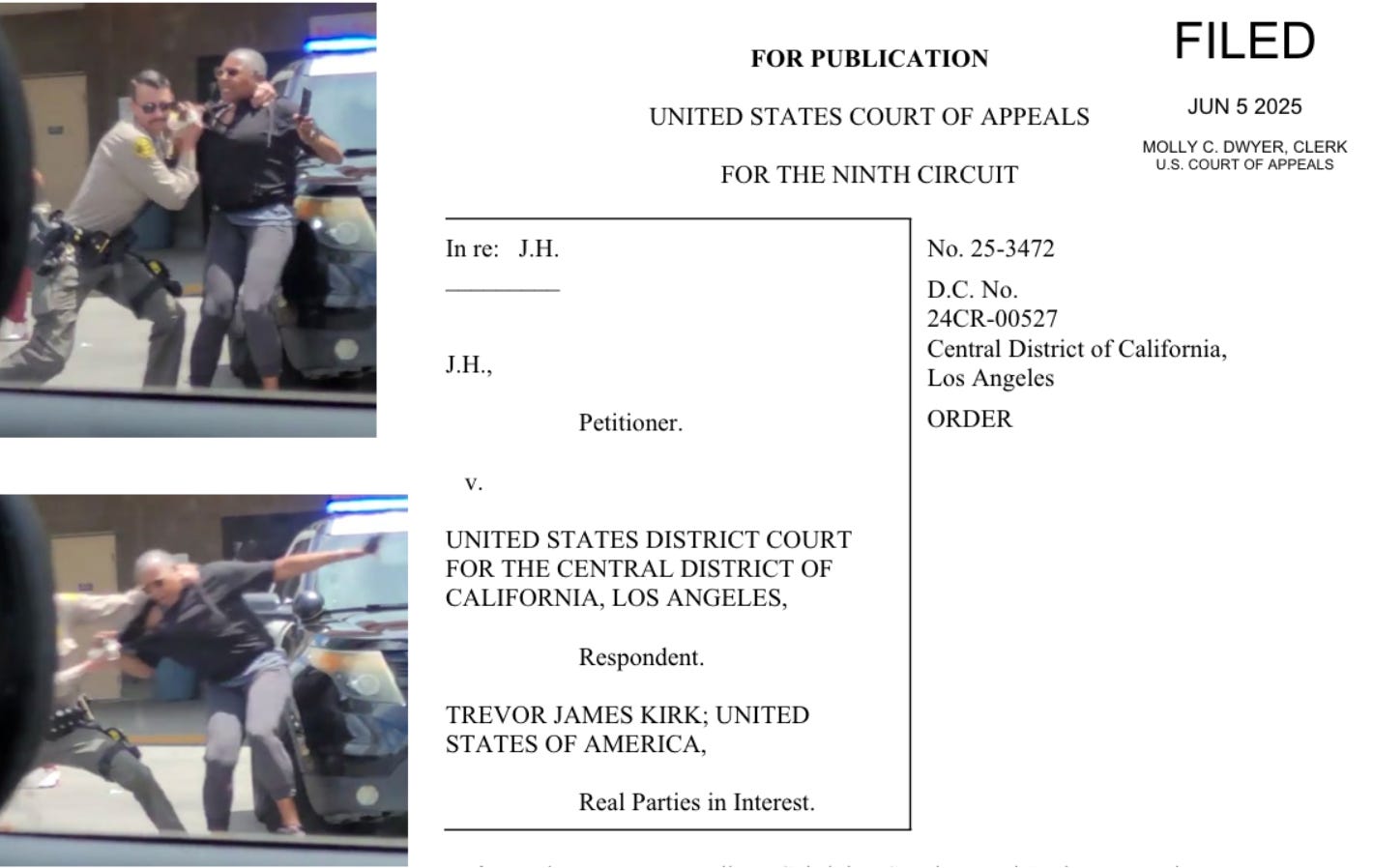

A federal judge sentenced a former sheriff's deputy to four months in prison after reducing his felony assault charge to a misdemeanor over the objection of the victim.

A federal appellate panel said Thursday that a woman assaulted by a Los Angeles County sheriff’s deputy has no legal avenue to challenge a judge’s decision to reduce his felony to a misdemeanor.

Hours after U.S. District Judge Stephen V. Wilson sentenced Trevor Kirk on Monday to…